Still Reading ‘Turkish Delight’ In the #MeToo Era? Yes, But With Reservations

Fifty years ago, Jan Wolkers shook the Netherlands to its foundations with Turkish Delight (Turks fruit). From the sixties onwards, the book’s explicit erotic descriptions made it a model of the sexual emancipation of a whole generation. But does the bestseller still deserve its status as a taboo-breaking classic? And how should we read the novel in the #MeToo era? Aleid Truijens blushed when she reread Turkish Delight.

The book was definitely better. Or so we thought. Although we had to admit, in 1973, that the film version of Turkish Delight was amazing. For a Dutch film, at any rate. Verhoeven’s film version of Jan Wolkers’ 1969 novel was to become the most successful Dutch feature film ever made.

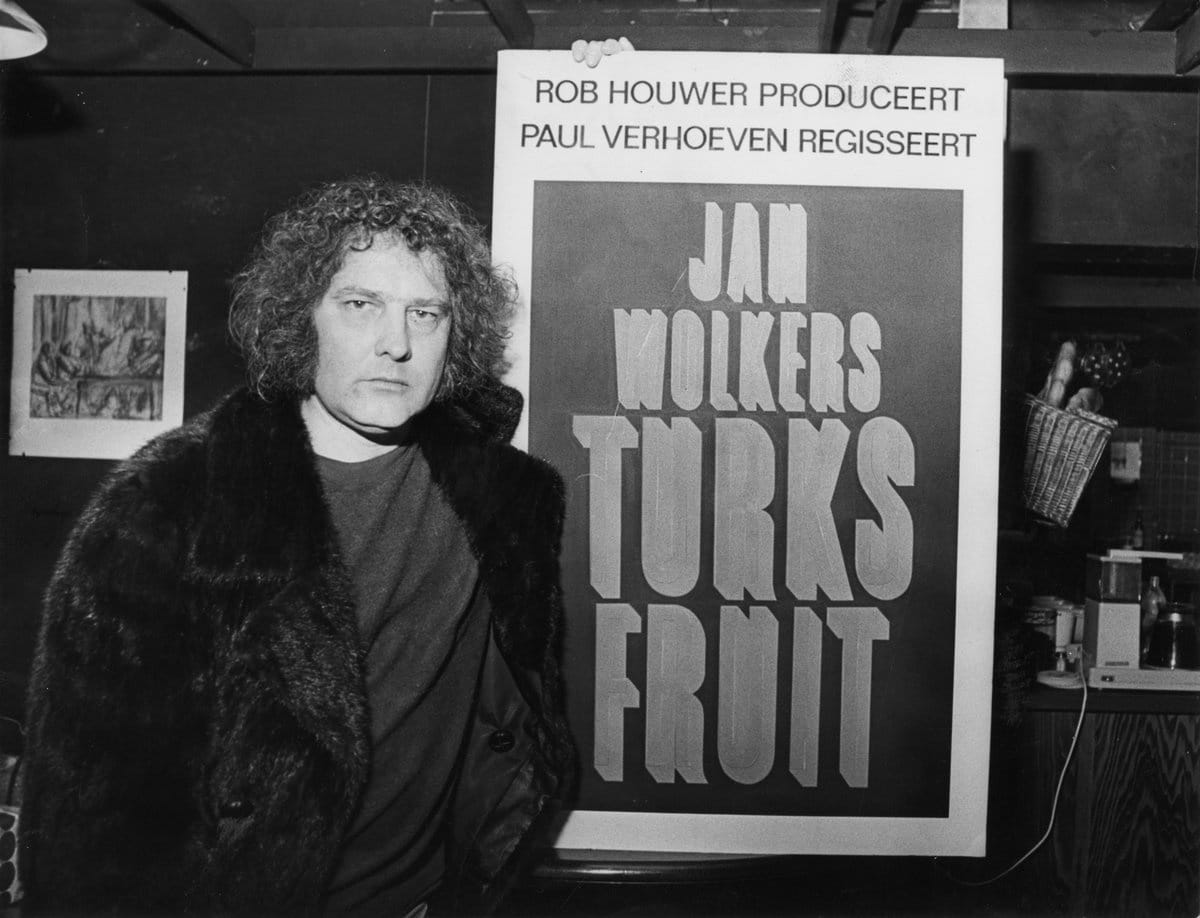

movie posters of 'Turkish Delight'

movie posters of 'Turkish Delight'The film played in our own hip, magical Amsterdam. It was about the liberated people we ourselves would have liked to have been, if we had not been so shy and ‘good’, and if we had had such godly bodies as the very young main actors, Monique van de Ven and Rutger Hauer. An appealingly unconventional, savage beast of an artist dragged women off to his lair and had his insatiable way with them. I went to see it with my first boyfriend, when I was sixteen. It was an inspiring evening. This was the way to celebrate love – the only way.

Titillating

But of course, it was Wolkers who thought it all up, not Verhoeven. Turkish Delight was THE book. Our book. This was the way a novel should be – the only way. Funny, raw, brazen, provocative, filthy, cruel, aggressive, sweet and heartbreaking. With Turkish Delight you learned something about sex before you even did it. For a moment, you were part of real life. Where people loved and betrayed each other like crazy.

Dutch and English cover of 'Turkish Delight'

Dutch and English cover of 'Turkish Delight'The great thing was that the young Dutch teacher in 4th year grammar school had recommended the book to us himself. If this was literature, then literature was brilliant. The teacher was full of praise for the Big Three – Mulisch, Reve and Hermans – as well, but they didn’t mean much to me then. There was just the one Big One. And he was a sculptor, too. With a sculpted head like the Emperor Nero.

Later I reread Turkish Delight regularly, when I was reviewing Wolkers’s diaries for the newspaper, for example. The last time was when Onno Blom’s biography of Wolkers, Het litteken van de dood (the scar of death), was published. According to his biographer, Wolkers was every bit as aggressive and possessive as his main characters. And yes, Turkish Delight was indeed very largely based on fact, although the woman who was the model for Olga, Annemarie Nauta, never succumbed to a brain tumour (that happened to another girlfriend).

Pornographic

Rereading it was a confusing experience. Even fifteen years ago, long before #MeToo, I could no longer understand what I had found so thrilling about it. Wolkers’ sex scenes are almost caricatures of pornography. I read sentences like ‘I tore the clothes off them and rammed myself silly’ and ‘I could see my rod pumping in and out between those two big, billowy white hills’. His descriptions of the lovers he got through after Olga’s departure are disgusting. They have ‘dry cunts with warts inside’, or ‘those contraptions with big labia dangling down like brown flappers, like the swinging doors of a saloon’. Nonetheless, he ‘impaled’ all of these women, because he has to find an outlet for his grief somewhere.

Rereading 'Turkish Delight' is a confrontation with one’s own naiveté and lack of critical capacity back then

The descriptions are so sexist and abusive that they hurt. And there is worse. Some of his bedmates act as free cleaning ladies. Once the business is done they mop the floor and scrub the loo – women’s jobs for which an artist has no time. Sometimes he has to put up with ‘the three runny-nosed pre-schoolers’ of a divorcee. Or he can only strike after listening to girls who ‘buried their snotty noses in the hair of your chest because they’d been raped by their father at the age of fifteen’ – tiring, you know, cry-babies like that.

More than anything else, reading Turkish Delight is a confrontation with one’s own naiveté and lack of critical capacity back then. How could I have thought at the time that such descriptions were strong, and swooned over such a caddish I-figure? I called myself liberated, even feminist. How could I have continued to read so much misogyny?

Annemarie Nauta, the woman who was the model for Olga in 'Turkish Delight'.

Annemarie Nauta, the woman who was the model for Olga in 'Turkish Delight'.© private archive Jan Wolkers

Now you might say that these hurtful descriptions of women come from a man who has been abandoned and is sick with grief and rage. I remembered the love between the I-figure and the adored Olga as very loving and heart-warming.

But even that was a disappointment when I reread it. Olga is, above all, the object of steamy lust, what she herself thought about it remains uncertain. We know that she is a very sweet, child-woman. She sleeps with her thumb in her mouth and eats so many ice creams that she has to throw up. She does not have to be awake for lovemaking. At night, her husband takes her ‘languid, apathetic body’ greedily; he thinks she is ‘numb from horniness’. During the day, Olga does little other than run around his studio stark naked, as his model. She neither works nor studies. There is no need for that.

We do not know why Olga runs away. But we do read that her husband slaps her as soon as she flirts with someone else. And that when he is at her parents’ house to talk to Olga, he overpowers her and when she starts to scream he presses his mouth on hers. We call that rape, but the I-figure thinks that his ex loves it.

I now feel that even the metaphor that drives a large part of the plot is cheap and heartless. The idea is that the relationship has been ‘poisoned’ by Olga’s mother, a witch of a woman, who wants to pair off her daughter with a rich man. Her disease, breast cancer, is the symbol of that perversion. Her ‘cancer-ridden tit’ became a gaping hole in her body. First the poison permeates Olga’s marriage, then her head. In Illness as Metaphor, in 1978, Susan Sontag offers a sharp analysis of how metaphors for cancer have influenced the way we think about cancer patients. They become symbols of evil. It is obvious that that is the case in Turkish Delight.

Obviously, times have changed. No one escapes the standards, the mores and the fashions of their time. The freedom of yesteryear sometimes turns out to be an enjoyment of power and bondage, one person’s liberation was the other’s oppression. But my intention is not to judge Wolkers, the writer that both men and women were crazy about in 1969, and whose world view they shared, by the standards of today, fifty years later, in the #MeToo era.

Achievements

Has the spirit of the sixties and seventies blown over, then? Has the once so liberal, broad-minded and tolerant Netherlands become prudish and conservative? I don’t think so. We cherish many of the achievements of those years: we can organise our own lives and most of us do not have to obey the demands of church and community. But feminism has only just reached maturity. Women are more self-confident now than hippie girls like Olga. They no longer accept the kind of treatment that she accepts from the narrator in Turkish Delight. And that kind of male is no longer considered attractive either.

Jan Wolkers

Jan Wolkersprivate archive Jan Wolkers

So, what is left of the literary hero of my youth? Well, certainly a memorable picture of the period in which he wrote; his rhythmic, no-holds-barred, flowery, expressive sentences, too. And I like the way Wolkers reconciled contradictions. He fitted perfectly into the youth culture of the sixties and seventies, and yet he grew up before the Second World War; a young man from a repressive Dutch reformed background, who suffered under the authority of a patriarch of a father, and an all-seeing, punitive God.

Wolkers spoke the language of rebellious young hippies, yet there was a hint of sanctimony in his work, too. His I-figures are apparently carefree artists, who have abandoned God and fulminate against big capital. But they are also tense young men imbued with a sense of guilt. They are cruel and tender, have a big mouth and a fearful heart. That dichotomy is moving. That is why I still like Jan Wolkers’s work. But with some reservations.

All quotes are from Sam Garrett’s translation Turkish Delight, Tin House Books (2017).